A fantasy novelette about two brothers, both obsessed with movies—one a not-very-successful screenwriter, the other an academic. When one dies from a drug overdose, his brother travels to Hollywood to make amends and find out what happened.

“But now, since I play Dracula, I am the bogeyman.”

—Bela Lugosi, December 11, 1951

My brother Denny died when I was twenty-six.

I got the call at 1:13 in the afternoon—which made it 10:13 in Los Angeles. I know this so precisely because I’d been at my manuscript all morning, lost in a dream of old Hollywood, and when the phone startled me out of my reverie, I glanced at my watch, as you do when you have been surprised awake. I was in my apartment, at my desk, the merciless August sunlight of east Tennessee molten in my windows. Denny and I had both fled the grim wastes of western Pennsylvania, seeking warmer climes. As soon as he’d collected his high school diploma, Denny had gone west, to California. Two years later, when I collected my own, I’d headed south. I sometimes thought he’d made the better choice, but that morning, when I picked up the phone, I was reminded otherwise.

The man on the other end asked if I was Benjamin Clarke.

“Ben,” I said.

The man paused as if the intimacy was unwelcome. When he spoke again—“Mr. Clarke,” he said—I recognized the flat, impersonal sympathy affected by all officialdom, from priests to principals, when bad news was to be delivered. I braced my hand against the desk, and when he started to introduce himself as Officer Something or Other I interrupted him.

“It’s Dennis, isn’t it?” I said.

It was, of course. I’d known it from the minute I’d heard that tone in the officer’s voice. He went on to describe the circumstances, but he needn’t have bothered. Heroin might have been the proximate cause. But it was Hollywood that killed him.

The way Hollywood has of grinding up its postulants was much on my mind at the time. For the better part of a year, I’d been working on my thesis, a study of Ed Wood and his bizarre entourage: Vampira and the Amazing Criswell, Tor Johnson and Bunny Breckinridge, the whole gang of oddballs and misfits, Bela Lugosi among them. In one way or another, Hollywood destroyed them all, but it was Lugosi’s doom that particularly interested me, then and now. It was Lugosi who had drawn me to study film in the first place. It was Lugosi who had drawn Denny to Hollywood.

Sometimes I think Lugosi must have dreamed of such a place before he even knew it existed—just as it was itself a dream, roused out of the slumbering dust by men who dared to seize life and pin it still breathing to a screen. It ate its history, and it feasted on hope. In Hollywood, even then, you were only ever as good as your last picture.

Lugosi came there in 1928. Already forty-six years old, he’d fled his father’s fists more than two decades before. Fled the cobbled streets of Lugos, where Hungary and Romania kissed. Fled most of all the profession that had been chosen for him. He did not want to be a banker, did not want even to be himself. He wanted to be no one at all. He wanted to be everyone. He wanted to be a star.

He’d worked his way to New York in the bowels of a merchant steamer. Broadway brought him fame, but even that fell short of his ambitions. So he took flight yet again, lured on by the glittering promise of the west. He fled until there was nowhere left to flee. He fled to Hollywood, and the sea.

Lugosi’s story is unique only in its particulars. In its broad strokes it’s the story of a legion of dreamers just like him: behind them some provincial misery, before them the promise of another self waiting to be born. It’s Denny’s story in a nutshell, and I guess it’s mine as well—but in the winter of 1969, when our version of the universal tragedy really began, Bela Lugosi served as midwife to our aspirations. Denny turned fourteen that year—I was two years behind him—and though Vietnam was in full swing, Nixon had just taken office, and the Steelers were still reeling from a 1-13 season, what mattered most to us that February was a TV personality named Gabriella Ghoul. Pittsburgh’s bodice-bursting answer to Vampira, Gabriella Ghoul had a starring role in both our onanistic fantasies and the local late-night creature-feature showcase.

Our mother disapproved of Gabriella and the creature features both, but Denny and I watched them anyway, sitting mesmerized on the threadbare carpet before the old black-and-white Zenith that we’d inherited from my grandparents when they upgraded to color. The movies Gabriella Ghoul introduced varied wildly in quality. If you got The Bride of Frankenstein one Saturday, you would get She-Wolf of London the next. But Lugosi’s Dracula—the only Dracula that really matters—stood apart from both the gold and the dross, sui generis.

It is in many ways not a great film. Dwight Frye’s effete, lisping turn as Renfield has not aged well and the visual language of the movie is static and stagy, with little in the way of camera movement. I can still remember our disappointment in the opening scenes that cold February night. We had been snowbound all day and had hoped for something really good—a rerun of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms or The Creature from the Black Lagoon—to alleviate our boredom. Instead we got this flat, hammy antique.

We were on the verge of turning the movie off and going up to bed when Lugosi made his first appearance, creeping down the vast, cobweb-shrouded steps of Castle Dracula, candle in hand. The powerful impression Lugosi made then renews itself every time I watch the film. I am twelve years old again, seeing for the first time his slow, deliberate gestures, listening anew to the broken cadence of his line readings, that inimitable accent, the timbre of his voice. Lugosi’s performance is broad—he never escaped his theatrical training; he was always playing to the back of the house—but his onscreen charisma is undeniable. His presence dominates every frame thereafter, and one leaves the movie thinking it is better than it actually is. Lugosi didn’t just play Dracula; Lugosi was Dracula.

I remember tearing myself away from the TV to look over at Denny. He looked gaunt and gray in the flickering blue radiance of the screen, his eyes deeply shadowed. He looked like he was already dead. In some sense, I suppose, he was.

Such were my thoughts as I boarded the plane at McGhee Tyson the following morning. I was routed through Atlanta and I managed to hold thoughts of Denny at bay until the long haul from Hartsfield to LAX. As the plane shuddered and wrenched itself free of the planet, it broke upon me that I was now entirely alone in the world. Our father had died in a mining accident when I was five and our mother had succumbed to cancer almost six years ago, not long after Denny left to chase his screenwriting dreams. I’d been seeing a girl in Knoxville, but both of us were pretty half-hearted about it. I’d left a message on her machine saying that I’d be out of town for a while, I’d give her a call when I got back, though I didn’t expect I’d really do so, and in fact never did.

I don’t mean by this to suggest that Denny and I were close. We weren’t. Even before our mother’s death, our dispositions divided us. Denny was reckless and I was not. He had some minor trouble with drugs in high school, and a few brushes with the law, also minor. I was always cleaning up his messes: shoving his laundry into the hamper, dragging him out of parties when he’d had too much to drink, and once, memorably, helping him bundle a half-naked cheerleader out his bedroom window. By the time he graduated high school, movies were the only thing holding us together—and even there our impulses differed. Mine was academic, his creative. I liked to tease scenes apart; he liked to storyboard new ones. When he left for L.A., we were already drifting into separate orbits. Mom’s death finished the job.

We talked two or three times a year after that, twenty minutes at most. Denny would share some hair-raising story or other, I would describe my latest academic enthusiasm, and then we’d sign off, fraternal duties fulfilled for another four or five months. We never talked about anything real. I had vague intimations that he’d hit some rough patches in Hollywood, but he never shared the details. He was more forthcoming about his fleeting moment of success, churning out scripts for a sitcom that never found its legs.

“It’s not a bad show,” he told me a few days after he landed the job. “Have you seen it?”

I had not.

“You should,” he said. “See what your older brother’s up to out here in Tinsel Town.”

So I watched a couple of episodes, more out of curiosity than any kind of sibling loyalty. The thing was called Girl’s Best Friend. It was about a twelve-year-old girl and a talking dachshund—really an alien in disguise, dispatched from his home planet to study earthlings. The dog was constantly getting into binds because it didn’t understand human customs. Or how to be a dog. People overheard it talking every other episode, initiating all kinds of frantic hugger mugger. The talking was accomplished by bad puppetry. You can imagine.

It was beneath my brother’s talents.

“It’s just a way to make ends meet until something better comes along,” he told me when I pointed this out. “The money’s great. I’m going to be making almost a thousand dollars a week.”

In 1980 this was big money indeed. But a TV writer’s job is perilous. When Girl’s Best Friend got its cancellation notice—it would come two years later—Denny would be unemployed again.

“I hope you’re planning to bank some of it,” I said.

Denny just laughed and changed the subject. That was the way it went.

The last time we talked, I told him my thesis was on Ed Wood. He was incredulous.

“Ed Wood?” he said.

My thesis director had asked the same question, in the same tone. At the time, Plan 9 from Outer Space was simply one of the worst films ever made. It had not yet begun to generate the cult of camp affection it enjoys today. My director felt that the project was a waste of my talents, and it was only with great reluctance that she’d signed off on the idea. But I was interested in the tragedy of Lugosi’s final years, and by then his fate had been inextricably bound up with Wood’s.

“Poor Bela,” Denny said when I explained this. The phrase had been Boris Karloff’s, or so the story went, and over the years it had become a kind of countersign, code for all the things that lay unspoken between us. Poor, poor Bela. Thinking of it now, as I winged my way across the country to untangle the mystery of my brother’s death, I felt something catch in my chest, and for a moment it was hard to breathe.

“Hey, you okay, buddy?” asked my seatmate, an older guy who’d been drinking gin and hogging the armrest for the last two hours.

“I’m fine,” I said. I wasn’t, though, and the question didn’t help.

It was the same question I’d asked Denny at the end of that final conversation. “Poor Bela,” he’d said, and there was something troubling in his voice. I couldn’t put my finger on it. Sadness maybe, or bitterness, or sorrow.

“You okay, Denny?” I asked.

“Fuck you, Ben,” he said. Six months later he was dead.

In his waning years, when he struggled to make ends meet in low-budget farces such as Bela Lugosi Meets a Brooklyn Gorilla, Lugosi often spoke of suicide. If this talk at first elicited sympathy and concern from Ed Wood and his band of happy misfits, they soon became tiresome exercises in self-pity. You can only cry wolf so many times.

This tension came to a head one evening in 1956 when Lugosi found himself in San Francisco, beating the drum for The Black Sleep, his first role in a major studio film in eight years. Yet even this modest comeback was a humiliation: once famous for his voice, Lugosi had been reduced to playing the mute valet of Basil Rathbone’s mad scientist. It was this, more than anything else, that led to his suicidal rumblings that night in the fourth-floor hotel room he shared with Tor Johnson, the behemoth former wrestling star who’d once billed himself as the Super Swedish Angel.

As the story goes, the Angel, tiring of Lugosi’s musings, knotted one meaty fist in the back of the old man’s Dracula cape. Gripping Lugosi’s belt with the other hand, Johnson thrust him out the open window. I sometimes imagined what the experience must have been like for Lugosi, looking down between his feet at the busy street below. The pedestrians on the sidewalk could not have suspected that only the Angel’s mighty hands, the strained seams of a cheap Dracula costume, and a stifled hiccup kept a drunken Hungarian from crashing down on them.

Picture it, if you can: the Angel crying in vexation, “Is this what you want, you damn hunkie?” and Lugosi swallowing, sobered. Inside, he’d pined audibly for an end to his sorrows; his new post outside the window must have imparted an altogether different perspective. The neck of his cape would have felt like a noose; when the Angel gave him a shake, the sidewalk would have wheeled far beneath him.

“Well?” the Angel is said to have bellowed.

“I think I vould like to come back in,” Lugosi reportedly said, and so the Angel hauled him back inside to face, once again, his reduced circumstances.

What a precipitous decline it had been. There had been a time when Lugosi’s name had been on every lip, when Universal had been inundated with fan mail for their new matinee idol. He’d had money, a sumptuous estate in the Hollywood Hills, a Buick Straight 8 Deluxe. In short, he had been a star. Biographers have sometimes wondered why a man of his stature ever took up with such crackpot scrabblers after Hollywood glory as Ed Wood and Tor Johnson. Most of them have concluded that he was driven by financial exigency. But I wonder if there wasn’t more to it, if Lugosi hadn’t been seduced by the myth of his own stardom, and if they hadn’t fed his need to fulfill that myth. Among Wood and his troupe of lunatic aspirants, Lugosi would have retained the sheen of Hollywood celebrity. If they represented the nadir of Lugosi’s career, he represented the zenith of theirs. The Super Swedish Angel must have admired him. Perhaps he regretted his fit of pique. Perhaps he told Lugosi that he stood at the threshold of a career renascence that would lift them all to the giddy heights of fame.

This is all a reconstruction, of course, colored by my own affection for Lugosi. There are multiple versions of the story; only in a few of them does the Angel actually dangle Lugosi out the window. In some, there are others in the room, men who were trying (and no doubt failing) to keep Lugosi sober for his next PR appearance. In one version, Lugosi’s rant occasions a desperate call back to Los Angeles, to Hope Lininger, Lugosi’s fifth wife.

“He’s threatening to jump,” the caller cried down the line.

“Then for God’s sake, open the window,” Hope is said to have replied.

I rented a Chevy Cavalier from Avis, threw my bags in the trunk, and caught the 105 east out of LAX. By the time I’d found my way to the 101 and the iconic Hollywood sign hove into view, my muscles were tense from negotiating the heavy Los Angeles traffic. But I still felt a thrill at seeing those nine letters strung across the slope of Mount Lee. Hollywood had always been more idea to me than geographical reality: a liminal threshold between what was and what could be willed into being, where Norma Jeane Mortenson could become Marilyn Monroe, Archibald Leach Cary Grant, and Marion Morrison John Wayne. Hollywood was a place where an impoverished Hungarian immigrant named Béla Blaskó could become Bela Lugosi.

In the end, of course, Hollywood had destroyed Monroe and Lugosi both—but it had also granted them a golden moment of stardom. The vast multitude of dreamers who washed up there weren’t even that lucky. They came in search of the selves they might become; they died in obscurity—or worse. In 1932, an aspiring actress named Peg Entwistle hurled herself to her death from the top of the Hollywood sign, a metaphor too obvious even for the silver screen.

Movies change lives.

That’s the fundamental axiom of my faith.

Unfortunately, they don’t always change them for the better.

I found Officer Something or Other—his name turned out to be Grant—at the Hollywood Station of the LAPD, a low brick building on Wilcox. He was gruff and gray, but not unkind. When I asked if I could see Denny’s case file, he sighed. “You don’t want to see that,” he said, and when I averred that I did, he shook his head and set me up in an empty interview room: one-way glass, green and white tile on the floor, an ammoniac smell of Pine-Sol. I sat at the battered table, and looked down at the file, a manila folder labeled with my brother’s name and a case number.

“Let me fill you in, instead,” Grant said from the door. “Some photos in there, you see them you can’t unsee them, you know what I’m saying. Maybe you don’t want to remember your brother that way.”

“I think I have to look,” I said.

Grant nodded. “If you say so.” He closed the door, and I was alone with the file. I hesitated, tempted suddenly to push it aside, to stand up and let myself out of the room, to catch the next flight back to Knoxville. Denny was dead. What more was there to know or do? I’d spent the first decade and a half of my life cleaning up his messes. Why not let someone else take care of this one?

Who knows why we do the things we do?

That’s one thing the movies always get wrong: the complexity of human motivations.

I opened the folder.

The police report was straightforward. A woman had called it in. She refused to give her name, and by the time the police had arrived at Denny’s apartment, she was gone. Denny had been dead for a while. The cause seemed obvious enough. He was on the sofa. The needle was on the floor at his feet. Grant had already told me they were just waiting for the toxicology report to confirm it.

I thumbed through the pictures. Maybe they wouldn’t have been so bad if I could have pretended that Denny was asleep. It wasn’t easy to do, though. There was something missing in the set of his face, some vital essence. I couldn’t put my finger on it then, and I can’t now. He was dead, that’s all. You didn’t have to look twice to know it.

I tapped the photos into alignment, slid them in behind the thin sheaf of papers and closed the folder. I found Grant in the squad room. He tucked the file away in a drawer. I took the seat beside his desk.

“You okay?” he asked.

That question again. I laughed without humor. “Sure. I guess so.”

Grant studied me in silence. A buzz of activity filled the room, low and electric: men talking quietly into phones, the hum of a photocopier, laughter from a counter by the coffee urn.

Grant had tracked my gaze. “Can I get you a cup?”

“No.”

“Good. Stuff tastes like battery acid,” he said. “Is there anything else I can do for you, Mr. Clarke?”

“Did he suffer?”

“Just went to sleep, that’s all.”

I thought about that for a while. There was suffering and there was suffering. I figured you didn’t stick a needle in your arm unless things were pretty bad.

“I’d like to see his apartment,” I said at last. “Am I allowed to do that?”

“Have to ask the property manager. We’re done there. I can call ahead, if you want.”

I said that I’d like that. Thanked him. Stood.

“Mr. Clarke.”

I turned to face him.

“How long has it been since you’ve seen your brother?”

“Two years.”

“You were close?”

“No.”

He nodded. “No use chasing ghosts,” he said.

But I didn’t have any other choice, did I? How else could I lay them down to rest?

By the time I wheeled the rental into the lot of Denny’s apartment complex, the buttery California light was melting into the arms of an enveloping blue dark. The shadows softened the utilitarian lines of the building, a repurposed motel, run-down and graffiti scrawled, the windows barred. An overflowing dumpster leavened the cool air with its reek. According to the sign out front, this was the Paradise Arms—the master stroke, perhaps, of an accomplished ironist.

I caught the manager as she was closing up for the day. She was weary and heavy-set, sixtysomething, kind. “I’m sorry for your loss,” she said as she led me to Denny’s apartment. “It’s an awful tragedy.”

She unlocked the door and turned on the light.

The place was a not unpleasant contrast to the squalor outside. The kitchenette, behind a waist-high dividing wall, was spotless, the living space clean and spare, without luxury aside from the TV—a 32-inch Panasonic with a matching VCR. The other furnishings had seen better days. A card table piled with books looked like it might collapse at any moment. The chairs were mismatched. The sofa sagged. A half-dozen video tapes in clear rental boxes stood atop a coffee table that could have been fished out of the dumpster outside. From the far wall, where Denny had taped up a poster of Dracula, Lugosi leveled his menacing gaze. Bela had brought Denny to Hollywood. It was fitting, I suppose, that when he died there, Denny had died under the failed Hungarian’s watchful eye.

“You’ll want to go through his things,” the manager said. Then, apologetically: “Sooner is better, of course.”

“Yes.”

“You could start in the morning—”

“Why not tonight?”

She glanced at her watch. “It’s nearly six. You’ll want to get to your hotel.”

“Perhaps I could stay here.”

I could see her thinking it through.

“Is the rent paid?” I asked.

The manager hesitated. “Through the end of the month,” she said. In divulging this, of course, she had already conceded. Five minutes later she pressed the key into my hand, and a moment after that I was alone in the apartment where my brother had died.

But it was Lugosi, as much as Denny, that I found myself thinking about that night as I sat sleepless in his living room, wired with jet lag. Denny had lost his battle with drugs; Lugosi had won his. In 1955, shortly before the debut of Bride of the Monster, his second feature with Ed Wood, Lugosi checked himself into Metropolitan State Hospital for morphine addiction. He was by then poverty stricken, emaciated by alcohol and drug abuse, despairing. Wood had pledged the premiere’s proceeds to defraying Lugosi’s medical expenses, but the opening-night profits, if any, must have been negligible—certainly inadequate to cover even a fraction of Lugosi’s costs. Despite Wood’s ambitions as an auteur, he had no talent or even competence as a filmmaker, and his posthumous fame as a camp icon was then inconceivable. It is one of the tragedies of Lugosi’s career that critics routinely rank his films with Wood among the worst movies ever made.

Nevertheless, Wood was a good friend to the former star, paying him regular visits at the hospital long after Hollywood had written him off, and promising him the lead in his next opus when there were no other parts to be had. Perhaps the scripts Wood showered him with provided Lugosi some comfort during the harrowing three months that followed. He later described his withdrawal from morphine as a nightmare of painful extremes: scalding fever one moment, glacial cold the next. At times, he could not bring himself to move. At other times, his limbs spasmed violently. He gnawed his blankets to fight the pain. He shat himself, a hot, reeking gruel down the back of his thighs, and he wept in shame as the nurses cleaned him up. Afterward, he struggled to the chair, humiliated, and watched them change his sheets with businesslike efficiency. “I want to die,” he moaned, and it was true: in that moment, he longed for nothing more than annihilation.

Yet he recovered, and when he left the hospital, he exited with one of Ed Wood’s screenplays in hand. “I’m looking forward to work again,” he told a reporter on the steps of the sanitarium. “I have an assignment playing the star part in Eddie Wood’s The Ghoul Goes West.”

But Wood could not get the financing to shoot the picture. Lugosi had played his final starring role. A little more than a year later, he died of cardiac arrest while taking an afternoon nap. Hope Lininger found him clutching a copy of Ed Wood’s unproduced screenplay. Hollywood had killed him a decade before. The heart attack merely made it official.

Poor Bela, Denny would have said. Poor, poor Bela.

But Denny, too, had died in thrall to the bitch goddess of the screen. He’d sacrificed everything to her: his ambition, his family, and finally his life. When Mom fell ill, I took a sabbatical from school and returned to Pennsylvania to take care of her. I hadn’t been home a week before the doctor told us she had six months if she was lucky. I called Denny with the news. “Come home,” I said.

“I will,” he promised, but the sitcom deal was just coming together, and he kept putting it off—one week and then two. The weeks piled up and turned into a month.

“You need to come, Denny,” I said. “She’s dying.”

“One more week,” he said, but there were no more weeks to be had. She died three days later.

Denny didn’t come home for the funeral, either. He’d been in the writers’ room of Girl’s Best Friend for less than a week and didn’t want to risk making a bad impression. Mom would have understood, he told me, and maybe she would have. But I spent the rest of the fall at home alone, seeing the will through probate, getting the house ready to put on the market, attending to the life insurance and a thousand other details. When all was said and done, the estate came to just over $80,000. I mailed Denny a cashier’s check for his half, and included Mom’s engagement ring as a keepsake—something to remember her by, since he seemed to have forgotten.

I talked with Susan Mazur, Denny’s agent, the next afternoon. She had an immaculate second-floor office in an old building, two blocks off Wilshire. I’d expected something altogether different: a high-powered Hollywood super-lawyer in a glass box downtown. William Morris maybe, or CAA. But of course Denny didn’t move in those circles. It had been three years since Girl’s Best Friend, and as I’ve said, that had been a middling success at best, commensurate neither with his ambitions nor his ability, which had apparently been considerable. He was good—“really good,” according to Mazur. “Hell, that was part of his problem,” she told me. “He thought he was too good for this town.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that show, the dog from space thing. I worked hard to get him in that room, and he blew it.”

“How?”

“The kid was a wreck. All he could talk about was you and your mother. It was a tough thing for him, losing your mom. After he quit—”

I sat back. “I thought the show was cancelled.”

“That was later. He lasted a couple months at most.” She gave me an appraising look. “He didn’t tell you?”

“No, I—He never mentioned it.” I’d always assumed that he’d lasted for the entire run. “What happened?”

“He decided talking dogs were beneath him. He should have stuck it out, saved the money against a dry spell, but—” She shrugged, sighed. “It’s hard to take in, isn’t it? What a terrible goddamn waste.”

“When did you see him last?”

“A month ago, maybe? Not long. He had this script he wanted me to look at,” she said. “Some kind of crazy biopic about Bela Lugosi. Not a commercial project. I have it around here somewhere.”

“Can I see it?”

“Why not,” she said. “Let me see if I can dig it up.”

She showed me to the door ten minutes later, still shaking her head in disbelief. And then I was outside, Denny’s screenplay in hand. I tossed it on the passenger seat of the Cavalier. I couldn’t bring myself to look at it. What kept coming back to me was how furious I had been when Mom had died and he’d decided to stay in California. What kept coming back to me was the conversation where I’d told him that talking dogs were beneath him. Now, I wondered why I’d found it necessary to share that insight. He surely didn’t need me to point out that he’d fallen short of everything he’d hoped to be.

In the months after my mother died, when the house seemed to echo around me, I probably saw two or three movies a week—virtually every film that showed up in the small town where Denny and I grew up. I felt something unclench inside me the minute I walked into the theater lobby. The ushers and projectionists soon knew me by name; the staff at the concession stand had my order waiting by the time I stepped up to the counter. But the really comforting moment came when the lights went down and I fell away from myself, lost in whatever dream flickered to life on screen. I watched without discrimination. I might see Piranha one night and The Deer Hunter the next, and both were fine by me. It didn’t matter what world the movie carried me off to, as long as it carried me away from that pinched and narrow Pennsylvania town—from the stark fact of my mother’s death, and my resentment of Denny for leaving me to tie off the loose ends of her life alone.

And even when I wasn’t at the movies, I was tuning in to them at home. There were still lots of films on network TV in those days: Johnny Weissmuller on Saturday afternoons and Shirley Temple on Sundays, and all sorts of made-for-TV movies, from The President’s Mistress to The Time Machine. And though Gabriella Ghoul was long gone, you could always count on catching a Hammer horror film after the late local news on Saturday night.

Movies, then. Movies to the last.

And it was a movie I needed when I returned to Denny’s apartment that night. I sat at the card table, eating takeout Thai and studying the books piled up around me. Most of them looked like research for the Lugosi screenplay: the standard biographies (Lennig, Bojarski, Cremer), plus a study of the classic Universal monster movies, two or three histories of Hollywood’s Golden Age, and a coffee table book featuring photos of Los Angeles in the thirties. But just then I didn’t want to read about movies. I wanted to lose myself in one. So after I put my leftovers in the fridge, I sat down to look at the videos on the coffee table.

I was halfway through the stack when I realized that the movie I was holding didn’t exist.

None of them did.

As far as I’ve been able to determine, Lugosi never met Gene Autry, the famed Singing Cowboy of the ’30s and ’40s. But during the last year of his life he was scheduled to star opposite Autry in The Ghoul Goes West, the Ed Wood film he’d mentioned on the steps of the sanitarium. This is not as implausible as it seems. Wood’s former roommate, Alex Gordon, who’d grown close to Autry, could well have brokered an introduction. And Autry might have welcomed the opportunity to work again. By 1956, his career was on a downward trajectory. He hadn’t appeared on screen in three years. He’d gained weight. He was drinking heavily. Hollywood had been extraordinarily good to him—he’d made ninety-three films between 1934 and 1953—but in the end she withdrew her favors. The proposed film never came about. Wood couldn’t get the financing. Autry backed out. Lugosi died, leaving Wood with a handful of test footage he recycled into Plan 9 from Outer Space, the camp classic that would cement his reputation as the worst filmmaker ever to square up a shot.

The entire episode earns only a single dismissive sentence in Lennig’s otherwise comprehensive Lugosi biography. It doesn’t even merit that in Autry’s 1978 memoir.

Yet the film I was holding—a commercially produced VHS tape—was clearly labeled The Ghoul Goes West. And it was not alone. A second glance through the stack confirmed that the other films were similarly impossible. They shouldn’t exist. They didn’t exist. They had never been shot. They’d been abandoned. But here they were. Here was the Orson Welles adaptation of Heart of Darkness. Here was Something’s Got to Give, Marilyn Monroe’s final film, left unfinished at her death. Here were Hitchcock’s Kaleidoscope, Clouzot’s Inferno, von Sternberg’s I, Claudius. A prank, surely. Someone had pasted fake labels onto the tapes—but why? To what purpose?

Retrieving The Ghoul Goes West, I glanced at the sticker on the case: Dimension Video. Then I turned on the television and slotted the tape into the VCR. The film opened with a black-and-white shot of the Amazing Criswell seated behind a desk, delivering a bizarre monologue about “the mysteries of the past which even today grip the throat of the present to throttle it.” The speech was portentous and theatrical, overcooked, the framing static. Then the image faded, to be replaced by a flat desert landscape with a saguaro cactus, obviously fake, on the right side of the frame. The credits came up on the left, each new name preceded by the sound of a pistol shot. Autry had first billing, Lugosi second, both of them above the title. The rest of the cast followed, among them Vampira and Paul Marco and Tor Johnson, Wood’s usual suspects. My only thought as the attribution credit came up—

Written Ÿ Directed Ÿ Produced

by

Edward D. Wood, Jr.

—was that I was looking at some kind of bizarre forgery. Then Lugosi, in full Dracula garb, appeared on screen, rising from a casket in a dim crypt that looked like a suburban garage. It was unmistakably him. By that point in my thesis research, I’d seen virtually every movie Lugosi had made three or four times. I knew the shape of his face almost as well as I knew my own. I recognized the trademark gesture as he turned to face the camera and swept his cape around to cover his mouth. A stroke of lightning split the screen. It illuminated a gothic castle set implausibly atop a desert butte—clearly a painted flat, executed with about as much expertise as you’d expect in a third grader’s school play. Another cut, and here was a posse of cowboys gathered around a campfire. In the shot that followed, Gene Autry showed up, stout and out of shape, possibly drunk. He was strumming a guitar and belting out “Back in the Saddle Again”—or trying to belt it out; his once-pleasant tenor was shot, and he was slurring his words.

I won’t try to describe the film that followed. It involved Lugosi, his vampire wife (Vampira, of course), and his mutant servant (Tor Johnson) menacing some rancher’s daughter, whom they wanted to impregnate (!) with their atomic ray (!). Autry and company rode to the rescue. It didn’t make much sense. But it wasn’t a forgery. Lugosi was undeniably Lugosi, Autry was unquestionably Autry. And the production was signature Ed Wood. The writing was incoherent, possibly the product of insanity. The production values were appalling.

Mesmerized, I watched the film straight through to the end, rewound it, and watched it again. The whole enterprise saddened me. This was Hollywood. Its most fervent acolytes were mired in delusion. Its fading stars clung to their former celebrity. If passion alone had been enough, Ed Wood would have been an auteur on the order of Orson Welles (though Hollywood destroyed Welles, too); if hunger were sufficient, Lugosi and Autry would have held the spotlight until they died.

After that I watched the other films. By the time I finished the last one, Inferno, it was nearly four. I rewound the tape, ejected it, and put it away, examining the plastic box for the second or third time. It was identical to the rental cases you saw everywhere in those days. Beyond the name of the store, there was no information to be had—no address, no phone number, nothing. The videos might have come from anywhere. They might have come from nowhere at all.

Denny’s alarm roused me, grainy eyed and exhausted, just past nine. I had one of those moments of psychic dislocation that you sometimes experience when you wake up unrested in a strange bed. For a breath, I wasn’t sure where I was or how I’d ended up there or why, and when it all came flooding back—Denny’s death and the long cross-country trek and the stack of movies that did not, that could not, exist—the whole series of events felt like some unfathomable dream. I sat on the edge of the bed for a long time. When I finally pulled things together enough to stand, I had to nerve myself up to face the movies in the next room. I was afraid they’d be there. I was afraid they’d be gone.

They were there.

I resisted the impulse to sit down and watch them through again immediately. Instead, I breakfasted standing in front of the open refrigerator, eating drunken noodles straight out of the box. After a shower, I felt almost human again. Human enough anyway to sit through the first fifteen minutes of Ghoul, to see if I could pick up anything I’d missed the first two times around. This was futile. There aren’t many nuances in an Ed Wood film. What you see is what you get. So I rewound the tape, ejected it, loaded it back into its box—and then, seized by some access of anxiety or paranoia, hid it away behind an old blanket on the upper shelf in Denny’s closet. Grabbing the video of Something’s Got to Give, I went looking for the manager in the old motel office.

She stood behind the counter when she saw me come in. She wanted to know how I was doing, if I was making any progress on Denny’s apartment. I lied on both counts, held up the video, said, “Do you have any idea where Dimension Video is?”

She pondered that, said the word Dimension aloud, as if that would help her remember. At last, uncertainly, she said, “I don’t know about Dimension. There’s a Video Hut a block over, by the laundromat.”

A Video Hut was useless to me, of course. I asked to see her phone book. Sitting on a hard plastic chair in the lobby, I checked it and checked it again, white pages and yellow pages, under both movie rental and video rental. Nothing, nothing, and nothing. If Dimension Video existed, it wasn’t trying very hard to get the word out. I sighed and handed the book back across the counter.

“You find what you’re looking for?”

The answer was no, in senses both literal and existential. I took a chance on the Video Hut. Maybe they’d bought the stock of a defunct store.

“I don’t think so,” the ponytailed kid behind the counter said. He squinted at the label on the box, then handed it back to me. “Sorry I can’t help. Maybe you should talk to the lady owns the place. Lou. I could take a message.”

“I’ll check back another time.”

“Your call,” he said. “Have a good day.”

I promised that I would try.

It was a fruitless endeavor, though. I dropped the video off at the apartment, climbed into the Cavalier, and spent the rest of the day touring L.A. I visited Lugosi’s star on Hollywood Boulevard. Had he lived to see it, Lugosi would have been thrilled at this affirmation of his achievements. But Hollywood took him to its bosom too late. He died mostly forgotten in a small apartment on Harold Way—the last stop on my swing through the city. I stood outside in the cool California evening, gazing at that apartment for a long time. I’d already tracked down Lugosi’s other homes, following the ascension of his star from the Ambassador Hotel to his mansion on Outpost Drive, where he lived at the apex of his fame in the mid-30s, and through its long decline in a variety of ever smaller accommodations during the ’40s and ’50s. But the Harold Way location struck me most powerfully. How could a man who had once commanded the adoration of millions wind up in such straitened circumstances, I wondered, and as I stood there in the blue twilight, watching the streetlights come on one by one to shed their soft refulgence, it seemed to me that the air filled with the inconsolable longing and desire of a city full of disappointed dreamers.

Denny’s screenplay was no biopic, because the Bela Lugosi it depicted never existed.

Bela Lugosi died in August 1956.

He did not shoot a film called The Ghoul Goes West in the spring of 1957.

He died clean. Despite all his faults, despite a failed career, despite his manifest deficits as a father and a husband, despite his despair, he never relapsed, and part of me despised Denny for depriving Lugosi of the one battle he had in reality won. Perhaps the first star to submit himself—publicly—to drug treatment, Lugosi left the hospital a changed man.

The Lugosi in Denny’s screenplay did not die in ’56. The Lugosi in Denny’s screenplay relapsed when Hope Lininger finally reached the limit of her endurance and abandoned him—which also never happened. In Denny’s screenplay, Lugosi, desperate for a fix and no longer able to find a doctor who would cooperate, turned to Tor Johnson. The Super Swedish Angel, who suffered from bad knees after his years in the ring, had no trouble getting a prescription. But he was a tormented man. Out of dog-like devotion, he procured Lugosi’s drugs; out of love, he begged Lugosi not to use them. Lugosi did, of course, and by the time The Ghoul Goes West went before the cameras, he was dosing himself regularly, sneaking away during breaks on the set to shoot up in the run-down studio’s lavatory—a filthy closet with a hollow-core door and a broken privacy lock.

It was in that lavatory that one of the key turning points in the screenplay occurred—a brief scene, but an important one: Lugosi is fumbling with a syringe when Gene Autry knocks at the door, saying, “Hey, is anyone in here?” Bela, startled, drops the loaded needle. It fetches up under the sink.

“If it will please you,” Bela says, “I will be just one min—”

But the Singing Cowboy has already barged into the bathroom, cradling a pint of bourbon. He’s pressing a drink on Lugosi—“Breakfast of champions,” he says—when he notices the syringe. He retrieves it, holds it up to the fly-specked light. “Hell, Bela,” he says, “I thought they got you off this stuff.”

“Yes,” Lugosi says, helping himself to a slug of the breakfast of champions. “So did I.”

Sitting there at the card table in Denny’s apartment, I sipped at a beer and turned the pages of the screenplay. The scenes sprang to life before me—Gene Autry’s discovery that his director is a transvestite (“Hell, son,” he says, “is that a skirt?”) and Lugosi’s developing conflict with his co-star. Bela, despite the morphine, is always the consummate professional. Autry, on the other hand, is a sloppy drunk. He forgets his lines; he misses his marks. Matters come to a head when they’re shooting the campfire scene that will introduce Autry’s character.

“Eddie,” Lugosi says to Wood, “horror picture is perhaps no place for singing ‘Back in the Saddle Again.’”

“But he’s the Singing Cowboy,” Wood protests.

Lugosi, too focused to notice that Autry has walked up behind him, says, “His voice, Eddie, it is not so good anymore.”

Eddie’s eyes widen. “Bela—” he says.

Too late.

Autry’s hand closes over Lugosi’s shoulder. When he turns, Autry’s face looms into his field of vision like a small moon, blotchy and cratered with pores.

“Why you son of a bitch,” he says. “You junkie, you ghoul.”

And then he punches Lugosi in the face.

Gene Autry’s Cowboy Code, a set of ten rules by which the Singing Cowboy’s young fans were to live their lives, expressly forbade socking seventy-four-year-old men in the jaw. “The cowboy must be gentle with children, the elderly, and animals,” Rule Number 4 read. I know this because Denny inserted the entire code as a title card into his screenplay. In the scene immediately following, he imagined a reconciliation between the two men. The slug line placed the action in the Cameo Club, the bar Lugosi—the real Lugosi—frequented in the final year or two of his life. To my knowledge no pictures of the place survive, but I have always imagined it much as Denny described it: dim and cool, with scuffed barstools and booths of buttoned red leather: an old man’s bar, quiet, little frequented, Lugosi nursing his bruised jaw with a cheap scotch when Autry sits down beside him.

“Have you come to punch me again?” Lugosi inquires.

“No.” Autry sighs. “Eddie said I might find you here.”

“I do not wish to be found.” Lugosi stands, dropping a handful of bills on the bar. “Good evening, Mr. Autry.”

“Stay a while, why don’t you?” Autry says, touching Lugosi’s elbow. “I’ll buy you a drink. Hell, I’ll buy you a dozen, if you like.”

“Please not to touch me,” Lugosi says, but he slides back onto the stool.

Drinks are ordered: bourbon, a top-shelf scotch.

Autry sighs, lifts his glass in toast. “It’s a slippery goddamn slope, isn’t it, Bela? One day you take a drink, the next you take two, and suddenly you can’t get through the day without the stuff.” He snorts. “You know what I mean?”

A bit of stage business follows. Lugosi takes out a lighter and lights one of his reeking cigars. He takes his time getting it going, turning the cigar in the flame until he has it burning evenly. He puts the lighter on the bar. “Bourbon, morphine,” he says. “It is the same. Sometimes, I think it would be better if I—” He shakes his head, draws on the cigar, expels a stream of noxious smoke.

“Sometimes what?”

“It does not matter. I am too much a coward.” Lugosi meets Autry’s gaze. “And you, Mr. Autry. What is it that you fear?”

Autry looks down. He turns his glass on the bar. “You know, Bela, I went to serve my country in the war. Flew C-109s over the Hump, and I was never afraid. But when I came back, Roy Rogers had taken over as the number one singing cowboy in America.” He shakes his head. “Irrelevance. I guess that’s what I fear the most.”

“You are a young man yet.”

“I’m forty-nine years old.”

“I was forty-nine when I played Dracula,” Lugosi says. “You have many lives yet. Me, I am an old man. Finished, as you Americans say.”

Autry laughs. “You Americans, huh? How long have you been in America, Bela?”

“A long time,” Bela says, and though Denny’s screenplay makes no such note—one of the limitations of cinema is that it has no access to its characters’ inner lives—I imagine Bela suddenly stricken with nostalgia for his native land. He had forever been a stranger to his adopted one. “Listen to my voice,” he says. “I am neither American nor Hungarian. I am always in between, a failure, a nothing.”

When Autry protests—“Now, Bela,” he begins—Lugosi waves him off. “You are a cowboy,” he says. “You are more than American, Mr. Autry. You are America. Me,” he says, “I am hunkie. I am failure. I am, as you say, a ghoul.”

I didn’t finish Denny’s screenplay—not then. I couldn’t bring myself to do it. Instead, I snagged another beer from the refrigerator, retrieved The Ghoul Goes West from its hiding place in Denny’s closet, and plugged the tape into the VCR. I couldn’t really concentrate, though. My mind kept drifting back to Denny. I wondered where he’d found the thing. I wondered what he’d thought of it.

I think that’s what I missed most after Denny disappeared into Hollywood: just chewing over old movies with him, finding out what he thought about them. He was the only person I’d ever known who could talk about the films I wanted to talk about. Don’t misunderstand me. My classmates in the master’s program were cinema geeks, too. But they wanted to discuss Buñuel and Visconti. Denny and I were more interested in O’Brien and Harryhausen. They read Film Quarterly. We subscribed to Famous Monsters of Filmland.

The last movie we saw together was Henry Hathaway’s 1947 film noir, Kiss of Death. Mom had been gone two years by then. I had just finished college with a more-or-less useless degree in English and had taken the year off to contemplate pursuing a still more useless degree in Film Studies. In the meantime, I was working in a video store and conducting a scattershot survey of film history, skipping around in the store’s collection at whim. I was in my blaxploitation phase when Denny called to say he was coming to visit.

“Why?” I remember asking.

“Just thought I’d catch up with my baby brother,” he told me. “That okay with you, Ben?”

“Sure,” I said. “Why not?”

Which is how he ended up in Knoxville a month later, crowding into my run-down apartment in Fort Sanders. In the week that followed, he slept late while I put in my hours at the store. After I clocked out, we ate delivery pizza, drank beer, and watched whatever we’d selected from the shelves for the evening. And talked movies, of course—what we’d seen, what we wanted to see, what we should see. Directors and leading men. Starlets and scream queens. The night before he left we wandered up and down the aisles, looking for something to watch. I pushed for Darktown Strutters. Denny made a case for Run Silent, Run Deep. We compromised on Kiss of Death, though we’d both seen it before. It had Victor Mature in one of his best roles, and we both loved Richard Widmark’s star-making turn as an unhinged, giggling psychopath named Tommy Udo. And of course it also had perennial heavy Brian Donlevy, cast against type as an assistant district attorney.

Donlevy had his own connection to Lugosi.

In 1952, after Lugosi fell on hard times, his then-wife, Lillian Arch, went to work as an assistant on Donlevy’s TV program Dangerous Assignment. Donlevy and Lillian soon became close. At one point Lugosi, drunk and stricken with jealousy, called the Dangerous Assignment production office, and demanded to speak with Donlevy. “That man is destroying my marriage,” he raved. Sober, he regretted his loss of composure, the latest in a series of self-inflicted humiliations, both personal and professional. The final blow came when Lillian left him less than a year later. Donlevy must have played a role in her decision—she would marry him in 1966, ten years after Lugosi’s death—but I think she loved Lugosi all the same. She’d stayed with him through two difficult decades, watching helplessly as he spiraled into morphine addiction, alcoholism, and poverty. Though he couldn’t see it, Bela was the one destroying the marriage, not Donlevy. He’d just worn Lillian out.

Denny disagreed. “It wasn’t Bela’s fault, not the way you mean. Those were symptoms, not the problem. If he’d made different decisions—”

“Like accepting the Karloff role in Frankenstein, I guess.” This line of reasoning was nothing new. Lugosi had famously declined the role. He didn’t want to endure hours in make-up every day. He didn’t want a part without lines. He didn’t want to be typecast as America’s bogeyman—though of course it was already too late for that. He was too old to be the leading man he’d hoped to become. His accent was too thick, the impression he’d made as Dracula too indelible.

Karloff, on the other hand, had accepted the role—had embraced it, and turned in a performance still stunning in its pathos. Frankenstein elevated him to stardom, and he made all the right choices thereafter. He embraced his role as the bogeyman, held out for good parts, and went on to enduring success.

Lugosi became Karloff’s shadow other self, Karloff what Lugosi might have been.

But Denny had another perspective. Turning down the role had been a life-changing mistake, sure—assuming he could have turned in a performance of Karloff’s caliber. But Bela had even then had it within his power to save himself.

“How?”

Stardom is a tricky thing, Denny told me. An illusion. Gossamer and moonlight. “You have to act the part,” he said. “No matter how dire the circumstances, you hang on to the fancy cars, you make yourself seen at the best restaurants, you date the most beautiful women. You project the illusion long enough, you become it.”

“The man was bankrupt in 1932,” I objected.

“The man was too proud to call in his markers.”

“What markers?”

“Bela was huge in 1932. He should have traded on that celebrity. All he needed to do was hang on for the right part. Instead, he sold himself short for the first thing that came along. He looked desperate. And desperation is fatal.”

“Whatever you say, Denny,” I said. “Come on—early day tomorrow.”

It was, too. We were up before dawn, off to the airport. It was raining lightly, and as the oncoming cars hissed by, shadows streamed across Denny’s face. He was quiet, pensive.

“What’s on your mind?” I asked.

Denny studied the strip malls as they slipped past. “I haven’t been entirely honest with you.”

“Okay.”

“I need money, Ben.”

“Money? Jesus, Denny, Mom left you forty thousand dollars.”

“You don’t under—”

“What about your talking dog? You made plenty of cash then, didn’t you?”

He sighed.

“Didn’t you?”

“Ben—”

“Answer me.”

“It’s gone,” he said. Then, gazing out at the line of mountains in the distance, dark against the brightening sky, he said, “It’s all gone.”

“What happened to it?”

“It’s like I said last night,” he replied. “You have to look the part, okay? You have to be the thing you want to become. After a while, I just couldn’t maintain the lifestyle. I kept waiting for the next break.” He laughed. “You saying you don’t have the money, Ben?”

“I work in a video store.”

“That’s not what I asked.”

“Yeah, I have it.” I hit the ramp for the airport exit too fast, and braked hard, the car leaning into the curve. “I need the money, Denny. I’m going back to school.”

“Right. Okay, then.”

A jet roared in overhead. I pulled to the curb at Departures. Traffic was just beginning to heat up. Taxis and shuttle buses, people smoking on the sidewalks. I got out and walked around the car and heaved Denny’s bag out of the trunk.

“You should come with me,” he said.

“You know that wouldn’t work.” I held out my hand. “Take care of yourself, okay?”

Denny ignored my hand. He pulled me into a hug. “You, too, Ben,” he said. And then, reaching for his bag: “But I guess I don’t have to worry about that, do I?”

He nodded and started off down the sidewalk. I watched him all the way through the sliding doors. He didn’t look back.

I never saw him alive again.

I kept knocking back beers until everything grew fuzzy and my vision narrowed to a dim tunnel. At some point I stumbled off to bed. I woke up after noon, hungover, my memory of the night before an oily void shot through with stark eidetic flashes—rewinding Ghoul for yet another viewing, trying to concentrate on Lugosi’s performance, though my focus slipped for seconds, minutes, half an hour at a time; sitting at the card table, staring blindly at Denny’s screenplay, as if the title page alone could reveal some truth or explanation that I hadn’t noticed before. But if any truth was there, I could not in the light of morning recall it.

I got up, scrubbed the moss off my teeth, and washed down a couple of Tylenol from the medicine cabinet. In the living room, I ejected Ghoul and returned it to its case. I swept a dozen beer cans off the kitchen counter. When I carried the garbage bag out to the dumpster, I saw that I’d parked the Cavalier halfway up on the sidewalk. I had a vague memory of going out for more beer. I was lucky I hadn’t killed someone.

I stashed Ghoul in its hiding place in Denny’s closet, and headed back out to the car. I spent the next couple of hours at a nearby mortuary, chosen for its proximity to the apartment as much as anything else. The undertaker was professionally solicitous. He expressed his condolences, asked about a burial plot, tried to sell me a casket and set up a service. I nixed the service and opted for cremation instead. I was out of there in less than two hours, but the experience brought Denny’s death home to me with a raw finality that transcended even that of the photos in the case file. I kept thinking about the way we’d been when we were kids, before we drifted apart—before Lugosi and the doom he’d brought down upon us.

I passed a park, and pulled over. The air was warm, but not oppressive, as it would have been in Knoxville. The foliage was in riotous bloom. I found a bench and turned my face to the sun, letting the warmth burn away the hangover. Denny’s words came back to me, paradoxical: to become the self you aspire to be, you must inhabit that self from the moment you imagine it into being. Maybe that had been the difference between us. I’d always been more or less content being me. Denny, for whatever reason, had longed to be someone else, had sacrificed everything on the altar of that dream. I wondered if he might have achieved it if I had given him the money he’d asked for. I’d been frugal with my half of Mom’s inheritance. It was true that I had planned to go back to school—had indeed done so—but it was also true that I could have spared at least enough to keep him going for a while. What might have happened then? What might he have become? And underneath these questions, others, troubling in different ways. How had he acquired the movies? And having come into possession of them myself, what was I to do with them?

Where was Dimension Video?

I had a small epiphany then: I’d never intended to return the movies, not really. How could I relinquish them? But I was desperate to see the rest of the store’s collection. Denny would have felt the same way, of course. For him, the desire might have been more pressing still. After a decade in Hollywood, he’d never seen a single word he’d written appear onscreen. But what if in some other time or place—some place where Ed Wood had gotten the financing to shoot The Ghoul Goes West and Marilyn Monroe had survived long enough to finish Something’s Got to Give—Denny too had found success? What if his own movies, the movies he’d only dreamed of, were waiting on the shelves of Dimension Video?

The question was absurd. Impossible. But, then, the whole thing was impossible.

I tried to puzzle out some sense or logic in it, some explanation for the entire episode, but by the time I returned to my car—hours later—no answers had presented themselves. I stopped for a sandwich on the way back to Denny’s apartment. Afterward—by impulse—I swung the car into the lot of the Video Hut. Maybe the owner was in.

She was.

The guy behind the counter directed me to an office at the back of the store. She stood when I introduced myself: a tall, angular woman in her thirties with a cap of close-shorn blond hair, not pretty exactly, but you wouldn’t soon forget her. Her name was Louise Roth—“but everyone calls me Lou,” she said, settling me in the molded plastic chair opposite her desk. She listened attentively as I explained my dilemma: my brother had left some rental tapes I’d like to return, but the rental boxes had no address or phone number—just a name, Dimension Video.

“Dimension Video, huh?”

“That’s right.”

“I’d let it go,” she said. “No one’s going to come looking for them. Lost tapes are the price of doing business. I’m sure you have bigger fish to fry with your brother’s death. What was his name? Danny?”

“Denny.”

“Right. Tall guy, dark hair, lived down at the Paradise Arms, is that right?”

“You knew him.”

“Not really. I remember him, though. He used to come in and pick up a movie once in a while. He had good taste.”

“What do you mean?”

“Most people, they want the new releases or the adult films. Your brother went a little deeper—he was always hunting up some obscure movie or other. Mostly we didn’t have what he was looking for. But he stuck around to talk once in a while. We both had a fondness for old horror movies. Not a lot of people want to talk about I Was a Teenage Frankenstein, you know what I’m saying?”

I laughed. “That was Denny, all right.”

“Funny thing is,” she said, “he came in not too long ago asking about Dimension Video himself.”

“Well, he seems to have found it.”

“Finding it wasn’t the problem,” she said. “Finding it again was another thing. He was looking to return the videos he’d rented there, and the place had just evaporated. So he said, anyway.”

“That doesn’t make sense. If he’d rented the movies there in the first place—”

“Exactly.” She leaned back in her chair, steepled her hands under her chin. “He said it specialized in hard to find stuff. Really hard to find. That true of the movies he left behind?”

“You could say that.”

“Care to tell me what you have?”

I hesitated. “You ever hear of an old Marilyn Monroe flick, Something’s Got to Give?”

“Doesn’t exist. Not the whole film, anyway. She died and they never finished it.”

“I know,” I said, and after that neither of us said anything at all.

Finally, I stood. I thanked her for her time.

She accompanied me out through the store. The evening rush was just beginning, the aisles filling up with nine-to-fivers looking for something light to kill the evening. I wondered what they’d think if they knew that somewhere out there a store called Dimension Video was renting out movies that didn’t exist. I suspected they wouldn’t much care. Lou, on the other hand—Lou walked me all the way out to the Cavalier.

“I’m sorry about your brother,” she said as I slid behind the wheel. “I don’t know what he was into—or what he’s gotten you into—but if that movie did exist . . .” She shook her head. “Well, I would give a lot to see it.”

“Thanks again,” I said. “Really.”

She stepped back. I closed the door, started the car, and pulled away. I glanced in the rearview mirror when I got to the light at the end of the block. She was still there, watching me.

There was a girl in Denny’s apartment.

I heard her when I swung open the door: a rustle in the gloom, a silence that felt like waiting. I switched on the light. Everything was as it had been: the books and the mismatched chairs, the TV, the video tapes stacked on the table. Imagination, nothing more, I thought, but I checked the bedroom all the same.

She was cowering on the other side of the bed—a slender blonde. I put her in her mid twenties. In that light it was hard to be sure.

“Don’t hurt me,” she said.

She said, “You look like Denny.”

She said, “I miss him.”

“I miss him, too,” I said, and the statement struck me with the force of revelation: I’d been missing Denny for years. I hadn’t even known it.

We ate at a diner down the street—Luke’s, a place that didn’t look much more promising than the Paradise Arms. Booths of torn green vinyl. Chipped plates and peeling laminate on the tables, a dead fly on the window seal. Fluorescent tubes buzzed overhead. In the flickering yellow glare, she looked weary and brittle, older than I’d thought she was, haunted by the ghost of her own beauty, which was utterly conventional. At home in Wisconsin, she’d have been a stunner. In Hollywood, she was just another pretty girl—and that was before time and care had begun to take their toll. Her blue eyes were dull, bracketed by fine lines, her lips pale, compressed by weariness. She was too thin in a town where it was impossible to be too thin.

Her name was Julie and she’d come to L.A. to be a star. She’d become a hostess at a steak house instead, making the round of open-call auditions for more than five years, in which time she had scored only one part—if you could call a single line (“Is that a dachshund?”) on Girl’s Best Friend a part. The only positive in the whole experience, she told me, had been meeting Denny, and even that was debatable. “He quit the show two weeks later,” she told me. “He said writing lines for a talking dog was beneath him.”

So there went that chance—for both of them.

She kept up with the auditions. He kept tinkering with screenplays. Eventually, they moved in together. I never knew anything about it, of course. So much of Denny’s life had been hidden from me. Another secret didn’t seem to matter.

“Was he using drugs?” I asked.

She shrugged. The shrug was eloquent. This was Hollywood. Weed, coke, pills, you name it: one thing led to another. Nancy Reagan could have predicted it. It hadn’t happened overnight, but when the money began to run out, they’d broken up. She wasn’t cut out for the Paradise Arms. She didn’t like heroin. She moved in with a girlfriend from the restaurant. She didn’t see Denny much after that. But she missed him constantly. She worried. She checked in two or three times a week.

“You were the one that found him, weren’t you?” I said. “You called it in.”

She sighed. “Don’t tell, okay,” she said. “Please. I don’t need the trouble.”

“How’d you happen to be there?”

“He called me. Said he wanted to say good-bye. I asked him want he meant, but he didn’t say. He just told me he loved me. He’d never said that before. Never. It scared me, so . . .” Another eloquent shrug. “I had a key. Just in case, he used to say. You never know. And when I let myself in . . .”

“He was gone?”

“Yeah.”

“So you’re saying it was intentional. Suicide.”

She pushed food around on her plate.

“Here’s the thing,” she said. “He was always leery of the stuff. He used clean needles. He was careful about dosing.”

“But why would he do it?”

“Why does anyone do it? You come here with all these plans, and you wind up seating tourists in a shitty restaurant instead. And the thing is, you can’t go home. Because you didn’t make it, right, and that’s the last thing you want anyone to know. This place is supposed to be paradise, but it feels more like purgatory to me. Everybody drifting around in limbo. I should have gone to college, become a nurse or whatever. An accountant.”

“It’s not too late.” This from the professional student.

“Sure it is,” she said, pushing her plate aside. “Listen, thanks for dinner, but . . .”

“Julie, why’d you come back to the apartment?”

She looked down. “There’s this ring,” she said. “He used to let me wear it on special occasions. It was like a thing between us.”

“You find it?”

She hesitated. And then, meeting my gaze, she dug into her pocket and laid it on the table between us. My mother’s engagement ring. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I just . . . I wanted a keepsake, something of Denny’s, you know.”

“Yeah,” I said. “I understand.”

I didn’t say anything after that, and she didn’t either. The clamor of the diner filled the air around us: the clink of silverware and the muted hum of conversation and someone calling out an order in the kitchen. I thought about Denny, all I didn’t know about him, all I never would. He’d told this absolute stranger to me—he’d told Julie—that he loved her. He’d called her at the end to say goodbye.

Our exchange at the airport came back to me. Take care of yourself, I’d said.

You too, Ben, he’d responded. But I guess I don’t have to worry about that.

I slid the ring across the table to her.

“Are you sure?” she asked.

“He’d have wanted you to have it,” I said, and I wondered if it was true.

Outside the diner, I asked her about the video tapes. She laughed. “You, too, huh?”

“What do you mean?”

“The last time I saw him, we had lunch. That’s all he could talk about. These movies he’d gotten ahold of. What’s so special about them, anyway?”

I pondered how to tell her that they were impossible, they didn’t exist. “They’re pretty rare,” I said. “Do you know where he found them?”

“He didn’t know where he’d found them.”

“What do you mean?”

“He said he rented them from this place near West 65th and Broadway. But he must have gotten the address wrong, because when we drove down there he couldn’t find the place.”

“He wanted to return the tapes.”

“I don’t think so,” she said. “I think he wanted more of them.” Then: “Listen, I have to run, okay. Like I said, thanks for dinner.”

“You mind giving me your number?” I asked.

She thought about it for a minute, and then she scrawled it out on the back of a receipt she dug out of her purse. She thrust it into my hand, wished me luck, and started off down the sidewalk in the opposite direction. When I called her a few days later, the number was out of service. I never saw her again, either.

We expect our movies—and I’m not talking about experimental films here, I’m talking about movies, I’m talking about Hollywood, I’m talking about stars—we expect our movies, we want our movies, to resolve themselves, perhaps because life so rarely does. Plot threads should be neatly tied off, character arcs completed. Consider the case of William Faulkner, who came to Hollywood in 1932 and returned, intermittently, for the next two decades. Faulkner turned out to have a genius for the movies. He received screen credit for just six pictures, but he put his stamp on many others. His single most famous movie, however—an adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep—achieved its notoriety in part because it doesn’t come together as neatly as we’d like it to. No one could ever figure out who killed the chauffeur—not Faulkner or his collaborators on the screenplay, not the director, not Chandler himself (“They sent me a wire asking me,” he later wrote, “and dammit, I didn’t know either”).

I include this anecdote because the conclusion of my own story—Denny’s story, and the story of the impossible movies that he left behind—is a lot messier than I would like it to be. The morning after I ate dinner with Julie, I drove down to West 65th and Broadway. Dimension Video wasn’t there. As far as I have been able to determine, it was never there. No one I’ve talked to recalls it. It does not appear in municipal archives. No business license exists. There are no tax records. I hunted for the place for weeks, broadening my search street by street. Nothing. It simply wasn’t there.

By the time I gave up, I realized that I’d given up on my thesis, as well. The Ed Wood I was writing about no longer seemed entirely real to me. There was another Ed Wood—a ghostly doppelgänger who’d directed a ghost of a film starring the ghost of a man who’d died of a heart attack a year before The Ghoul Goes West ever went into production. I couldn’t sort out who was real and who wasn’t. All I know is that I camped out in Denny’s apartment so long that I ended up taking over the lease. A month passed, and then another. I ate takeout pizza. I ate Chinese. I ate at Luke’s. I drank too much beer. I drank until I was sick of myself, and then I woke up hungover one day and poured all the booze in the apartment down the sink. I showered, ate a slice of cold pizza, and walked to the Video Hut. Lou was in her office.

“I have some movies I think you ought to see,” I told her.

We watched them that night on the sofa where my brother died. She gazed at the flickering images in rapt silence. “Where did these come from?” she asked at one point, never taking her eyes from the screen. “I don’t know,” I said. After that, Lou and I took up the search for Dimension Video together. Somewhere along the way we started seeing each other. I suppose it was only a matter of time. We have a lot in common—almost as much as Denny and I did.

Which brings me back to Denny. Denny and Lugosi.

In the final scenes of Denny’s screenplay, Ed Wood wraps The Ghoul Goes West and the cast retires to the Cameo Club to celebrate. Autry buys rounds for everyone—“I have plenty of money, anyway,” he tells Lugosi—but is otherwise morose. Bela shares his dolor. “I have not even that solace,” he says, and though the screenplay doesn’t describe his thoughts, one can easily imagine him ruminating about the cramped apartment on Harold Way. Awash in morphine and Autry’s top-shelf scotch, he might have drifted for a time, lost between Hungary and Hollywood, the career he’d had and the career he could have had, scraps of old dialogue straying through his mind: Listen to them, the children of the night, what music they make and I never drink wine and, most of all, I am Dracula, the phrase that had made him a star. Perhaps he would have recalled a fragment of his monologue from Bride of the Monster, the previous picture he’d made with Eddie Wood. Home? he might have said. I have no home. Hunted, despised, living like an animal! The jungle is my home. But I will show the world that I can be its master!

Except he couldn’t, of course. The world mastered him. Denny’s screenplay ends with Lugosi’s death—not from the heart attack that killed him in reality, but from a deliberate morphine overdose. He’d found fame as Dracula, but his success never reached the height of his ambition and he spent the rest of his life watching it slip away.

Denny wasn’t even that lucky. He squandered his moment. He would write no talking dogs. Hollywood killed him as surely as it had killed Lugosi before him.

And me?

Ten years further on, and I’m still here. I work behind the counter at the Video Hut these days. Lou and I do what we can to steer our clientele to the films that matter most to us, but it’s the new releases and the adult videos that keep the lights on.

And I guess that’s the end—except for the matter of Denny’s ashes. They came back to me in a cardboard box the size of a shoebox. I opened it up one time, expecting, I suppose, a fine gray powder. It was coarse and granular instead, with whitish-gray fragments that could only be bone. They would have made a fine prop for a Bela Lugosi movie. Irony: it’s good for the blood, Gabriella Ghoul would have said. And with that I closed up the box again. It sat on the chest in Denny’s bedroom for several months before I drove it down to Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, where Lugosi is buried in the Dracula cape he could never seem to shrug off in life. I scattered a handful of ashes there. The rest I scattered at the base of the Hollywood sign during a midnight expedition up Mount Lee. The sign isn’t as impressive as you think it will be when you see it close up—but nothing ever is, is it?

When I was done, I thought about Peg Entwistle and I thought about Lugosi and I thought about the movies that couldn’t possibly exist back home in my apartment. But they did exist. Somewhere, in some other place than this, those movies were made. Somehow they wound up in Denny’s possession, and that’s enough to give me hope. I like to imagine that there’s a place where Peg Entwistle became a star, where Bela Lugosi became the leading man he’d aspired to become, and where my brother Denny still survives, living up to the measure of his dreams.

Copyright © 2018 by Dale Bailey

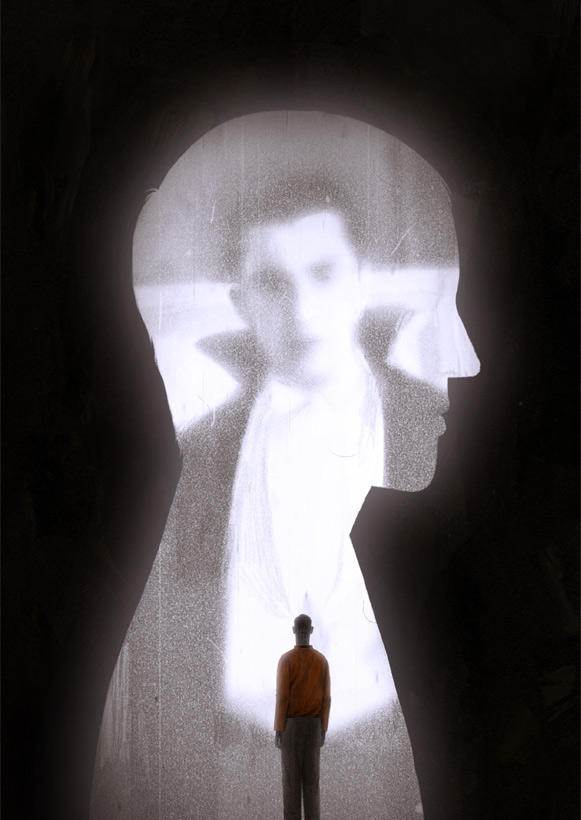

Art copyright © 2018 by Dadu Shin

Buy the Book